U

The Citroën Guide Steering: DIRAVI Steering 40

DIRAVI Steering

Another gem of engineering, the DIRAVI steering,

made its debut on the SM, excelled in many CXs

and the flagship, V6 XMs (left hand only, the

small amount sold in the UK never justified the ex

-

penses of the conversion to RHD).

The DIRAVI (Direction Rappel Asservi, Steering with Limiting

Counterforce) steering is as unique as the hydropneumatic

suspension—it was never used by any other manufacturer,

although its excellence over conventional power assisted

systems speaks for itself.

As usual, it has some quirks confusing the average driver

during their first meeting. First of all, it is geared very high:

it only took two turns of the steering wheel from lock to

lock (one turn for each side) to steer on the SM. Later mod

-

els, the CX and the XM retained this feature although the

number of turns was larger (2.5 and 3.3). The gear ratio

could have been much higher, the engineers themselves in

-

sisted on a single turn lock to lock for the SM (which would,

interestingly, void the need for a circular steering wheel

completely). The final solution was a compromise to reduce

the initial strangeness of the steering for the drivers already

accustomed to traditional systems.

Certainly, making the gearing so high is not complicated

in itself but a conventional (even power assisted) system

with such rapid response would be unusable. As the car ob

-

viously has to have a similar turning circle as other cars, too

responsive a steering would mean that even the slightest

movement of the steering wheel would induce excessive de

-

viation of the car from the straight line. To avoid this, it uses

an opposing force, increasing with the vehicle speed. With

this setup, in spite of the very high gearing, it is very easy to

use it during parking, yet it offers exceptional stability at

high speeds: it actually runs like a train on its rails, requiring

a sensible amount of force on the steering wheel to deviate

it from the straight line. And an additional feature: the steer

-

ing wheel (and the roadwheels, naturally) center them

-

selves even if the car is stationary.

Second, there is no feeling of feedback from the road

through the steering wheel. Other steering systems have a

constant mechanical connection between the steering

wheel and the roadwheels, the DIRASS only adds some

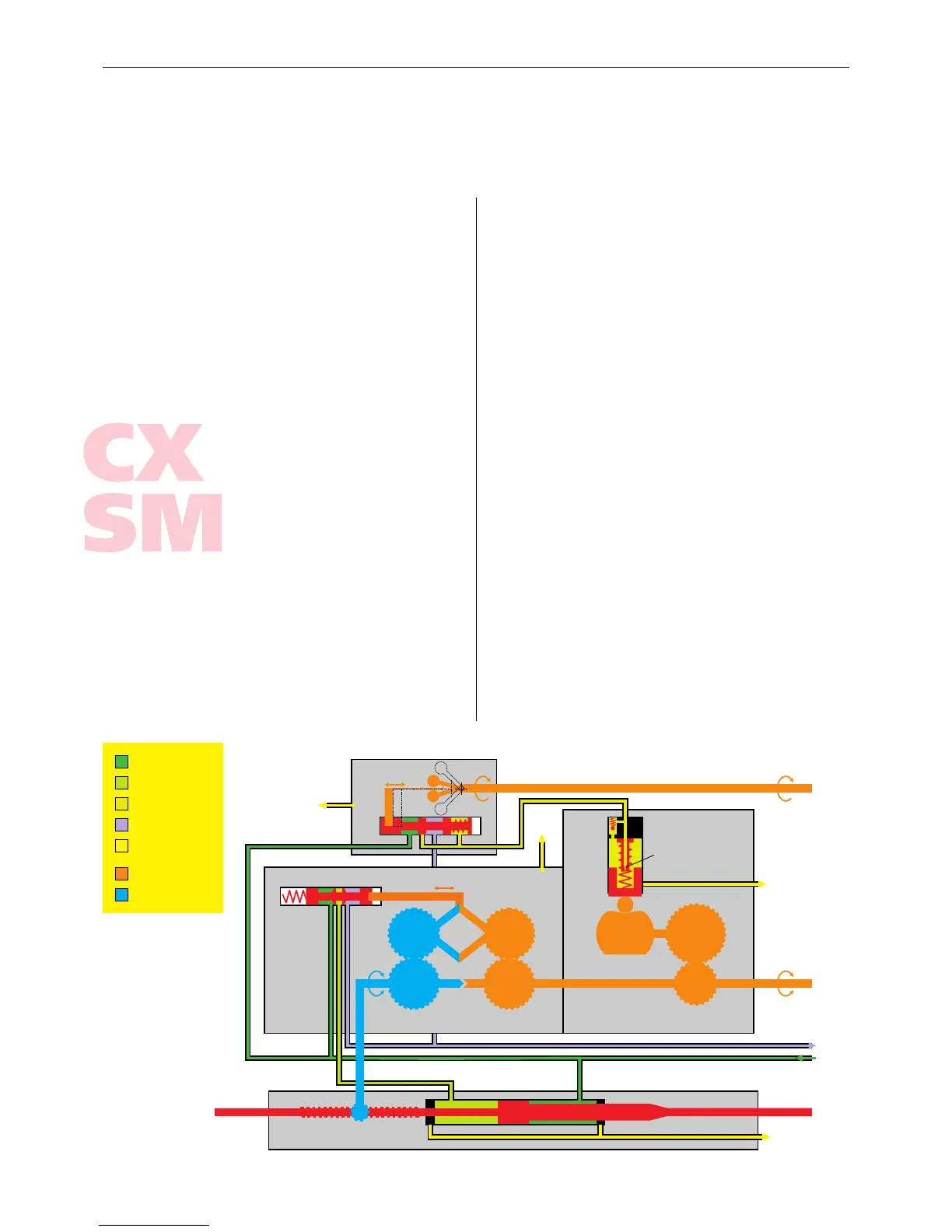

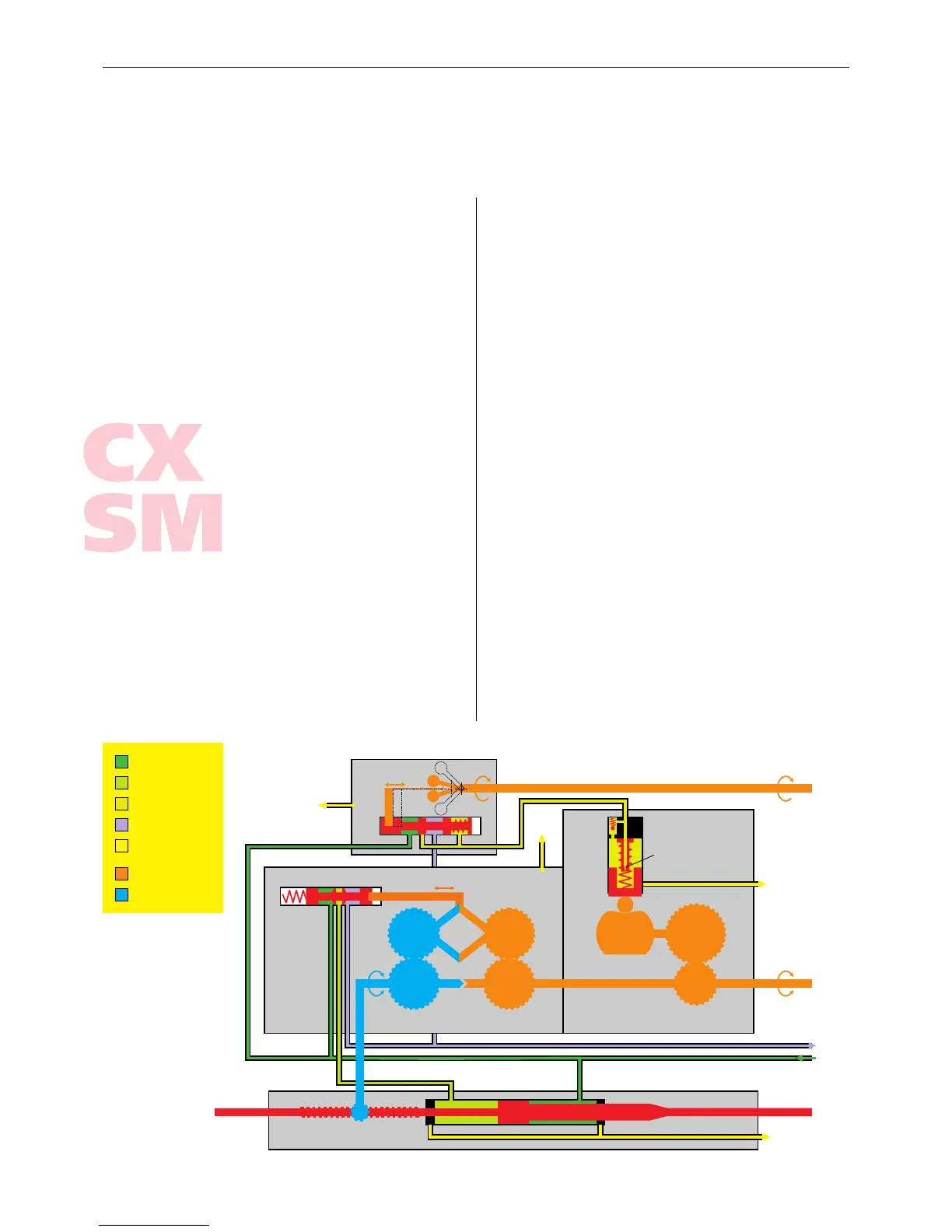

force to the one exerted by the driver. DIRAVI is different:

simply put, the usual path between the steering wheel and

the steering rack is divided into two halves, with a hydraulic

unit in the middle. When the driver turns the steering

wheel, this only operates the gears and valves in the hydrau

-

lic unit. The hydraulic pressure then moves the steering cyl

-

inder and the roadwheels. The lower half of the mechanics

works in the opposite direction, as a negative feedback, re

-

turning the hydraulic system to the neutral position as soon

as the wheels reach the required direction. The hydraulic cyl

-

inder and the wheels become locked, no bump or pothole

can deviate them from their determined direction. Note

that this neutral position is not always the straight-ahead di

-

rection, the hydraulics return to neutral whenever the steer

-

ing wheel is held at a given angle for any longer period of

time. Letting the steering wheel rotate back or turning it fur

-

ther in the previous direction will initiate a new mechanical-

hydraulical cycle as described above.

Loading...

Loading...