2005 MASTERCRAFT OWNERS MANUAL–PAG E 16-3

Battery electrolyte fluid is dangerous. It contains sulfuric acid, which is poisonous, corrosive

and caustic. If electrolyte is spilled or placed on any part of the human body, immediately

flush the area with large amounts of clean water and seek medical aid.

• Use a battery terminal cleaning brush to remove corrosion from the inside of the battery terminals. Clean the terminals with a

water-and-baking-soda solution and rinse.

• Reconnect the positive terminal first, then the negative. Tighten the terminals. Coat both terminals completely with a thin

covering of marine grease. Be sure that the rubber boot covers the positive terminal completely.

Note: Your engine is designed to work with the standard electronics installed in your boat. If you add other electrical

components or acccessories, you could change the way the fuel injection controls your engine or the overall electrical system

functions. Before adding electrical equipment, consult your dealer. If you don’t, your engine may not perform properly.

Add-on equipment may adversely affect the alternator output or overload the electrical

system. Any damage caused as a result will not be covered by, and may void, your warranty.

If you ever need a replacement battery, be certain to select a marine battery with at least 750 cold-cranking amps at zero

degrees Fahrenheit. Before disconnecting the battery, make sure the ignition key and all accessories are in the OFF position. Also

remember to re-attach the cables correctly, with the negative cable connected to the negative or (-) post and the positive cable

connected to the positive or (+) post.

When charging, batteries generate small amounts of dangerous hydrogen gas. This gas is

highly explosive. Keep all sparks, flames and smoking well away from the area. Failure to

follow instructions when charging a battery can cause an electrical charge or even an explosion

of the battery which could cause serious injury or death

MasterCraft recommends the use of a spiral cell type battery, such as the Optima brand. These batteries exceed most other

batteries in holding and extending a charge.

INSPECT THE ENGINE

FOR LOOSE OR MISSING HARDWARE

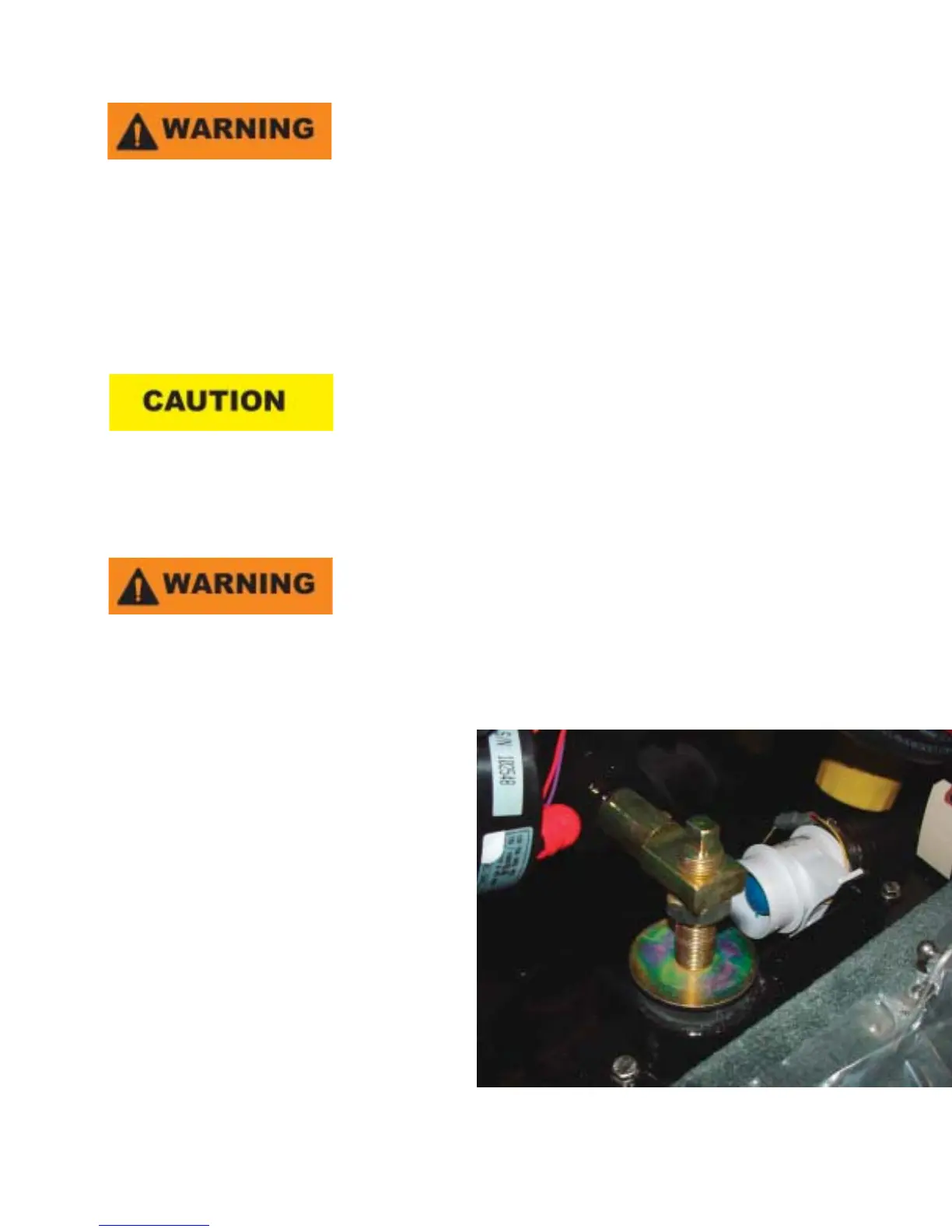

Because this process should be completed while the en-

gine is cool and cannot cause burns to your skin, we recom-

mend you do this before starting your boat.

Step 1: Ensure the engine is OFF and the engine safety start-

ing switch disconnected. Be certain that the throttle/shift con-

trol lever is in neutral. Open the engine compartment and vi-

sually inspect the engine.

Step 2: Systematically check the entire engine for loose

and missing hardware. Try to shake components by hand

such as the alternator and the motor mounts. If a loose-

ness problem exists, see your MasterCraft dealer.

Loading...

Loading...