Chapter 15 - Making your programs work

There is more to the art of programming computers than just knowing which statement does what. You will

probably already have found that most of your programs have what are technically known as bugs

when

you first type them in: maybe just typing errors, or maybe mistakes in your own ideas of what the program

should do. You might put this down to inexperience, but you would be deluding yourself.

EVERY PROGRAM STARTS OFF WITH BUGS.

Many programs finish up with bugs as well. There are two corollaries to this; first, you must test all your

programs straight away; & second, there's no point in losing your temper every time they don't work. The

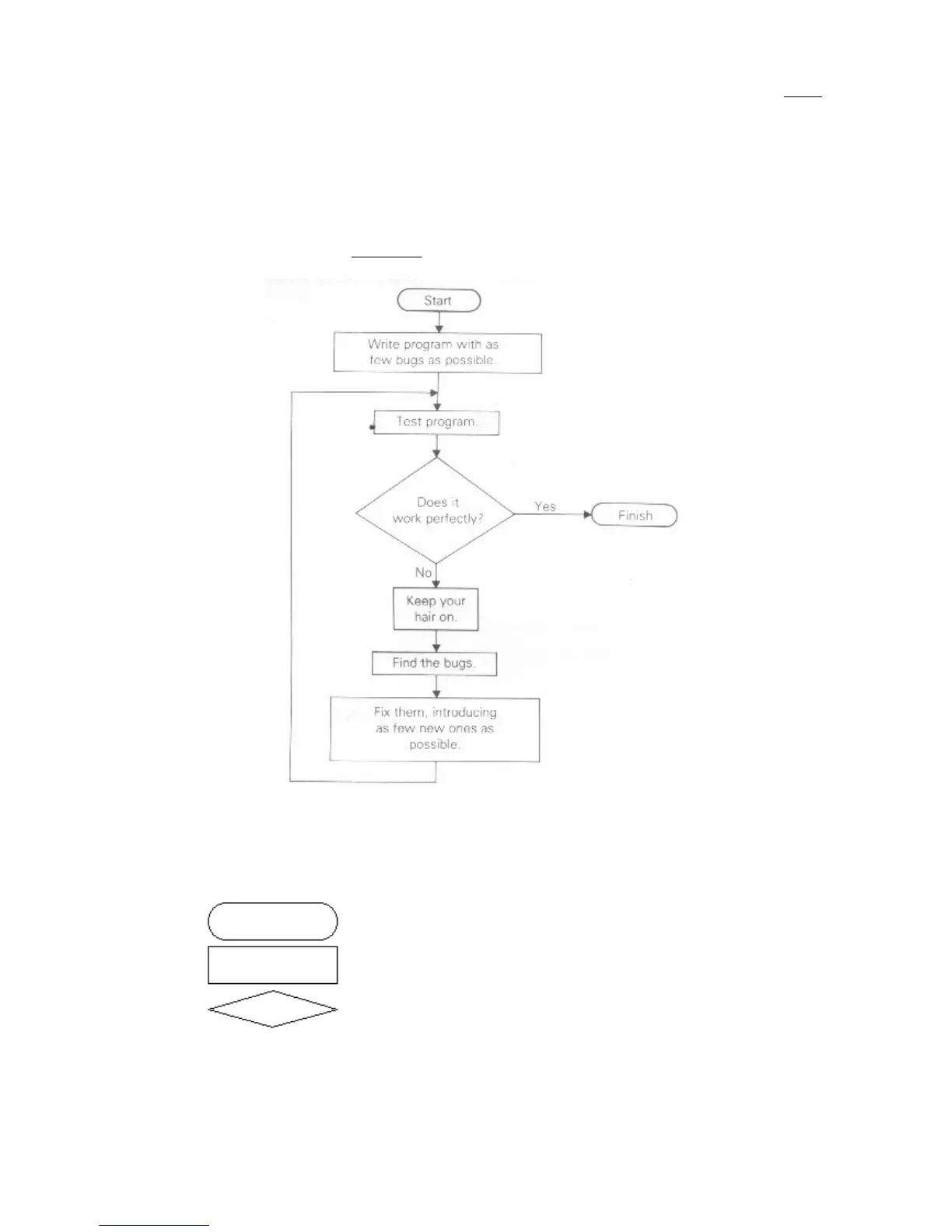

general plan can be illustrated with a flowchart:

The idea is that you follow the arrows from box to box, doing what it says at each one. We have used

different sorts of boxes for different sorts of instructions:

(These shapes are fairly widely used, but nothing earth-shattering depends on them.)

Of course, these flowcharts are ill-adapted for describing human activities; thinking along fixed straight

lines like this is not good for creativeness or flexibility. For computers, however, they are just the job. They

are best at describing the large-scale structure of programs, with a subordinate in almost every box, so a

flowchart for our sterling example in the last chapter might be.

A rounded box is start or finish.

A rectangular box is a straightforward instruction.

A diamond asks you to make some kind of decision before carrying on.

Loading...

Loading...