SYS-APG001A-EN Dedicated Outdoor Air Systems: Trane DX Outdoor Air Unit 1

Defining the

Dehumidification Challenge

Building professionals expend much time and effort to design HVAC systems

that handle both ventilation and dehumidification. High-occupancy spaces,

such as classrooms, pose a particular challenge—especially when the system

of choice delivers a constant-volume mixture of outdoor and recirculated

return air. Why? The answer lies in the fact that the sensible- and latent-cooling

loads on the HVAC equipment do not peak at the same time.

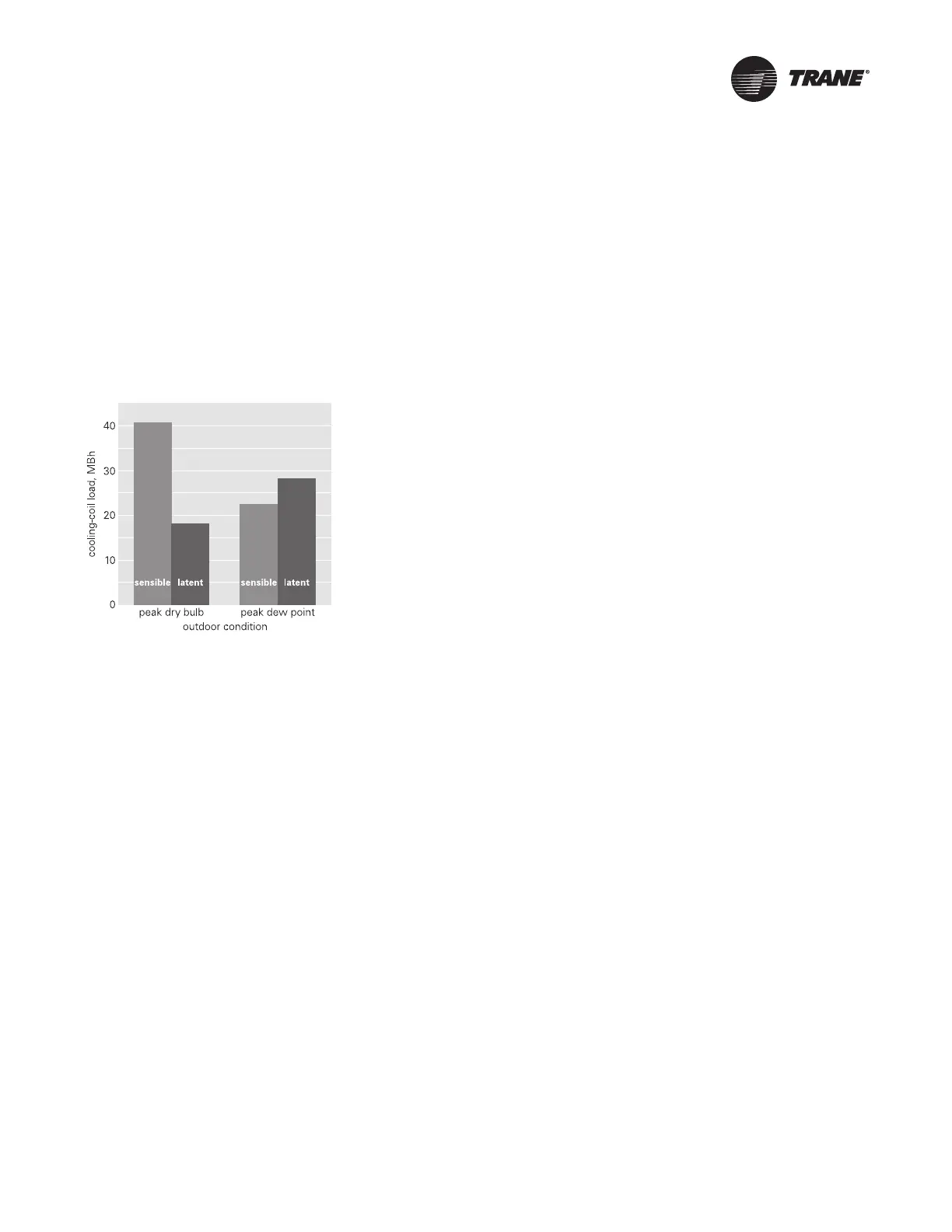

When it’s hot outside, the sensible-cooling load often far exceeds the latent-

cooling load (Figure 1). By contrast, when it’s cooler but humid outside, the

latent-cooling load can approach or even exceed the sensible-cooling load.

Conventional HVAC equipment traditionally is selected with sufficient cooling

capacity to handle the design load at the peak outdoor dry-bulb condition and

controlled by a thermostat that matches the sensible-cooling capacity of the

coil with the sensible-cooling load in the space. Therefore, as the sensible-

cooling load in the space decreases, the cooling capacity (both sensible and

latent) provided by the HVAC equipment also decreases. In most climates, the

combination of less latent-cooling capacity and a lower SHR (sensible-heat

ratio) in the space elevates the indoor humidity level at part-load conditions.

An “off-the-shelf,” packaged unitary air conditioner may further aggravate this

situation. Such equipment is designed to operate with a supply-airflow-to-

cooling-capacity ratio of 350 to 400 cfm/ton. In hot, humid climates, offsetting

the ventilation load for high-occupancy spaces may require that the unit

delivers no more than 200 to 250 cfm/ton in order to achieve the dew point

needed for adequate dehumidification.

Figure 1. Cooling loads at different

outdoor conditions*

* Based on an example classroom, which is

l

ocated in Jacksonville, Fla., and has a

target space condition of 74°F dry bulb and

50% relative humidity

Loading...

Loading...