Page 9Page 8

2.6 Rudder Movement (Gain)

The Wheelpilot uses highly advanced steering soft-

ware, which constantly assesses how the vessel is

being affected by the prevailing conditions. By

adjusting its own performance, the pilot is able to

maintain the most accurate course for these condi-

tions, just as a human pilot would. Thus, in a rough

sea the pilot is not overworked and battery drain is

kept to a minimum.

The pilot will make corrections to compensate for

heading errors, in order to keep the boat on course.

The amount of rudder correction made is set by the

Gain (sometimes referred to as the rudder ratio).

The Gain setting can be compared to driving a motor

vehicle - at high speeds, very little wheel movement

is necessary to steer the vehicle (LOW gain). When

driving at slow speeds, more wheel movement is

necessary (HIGH gain).

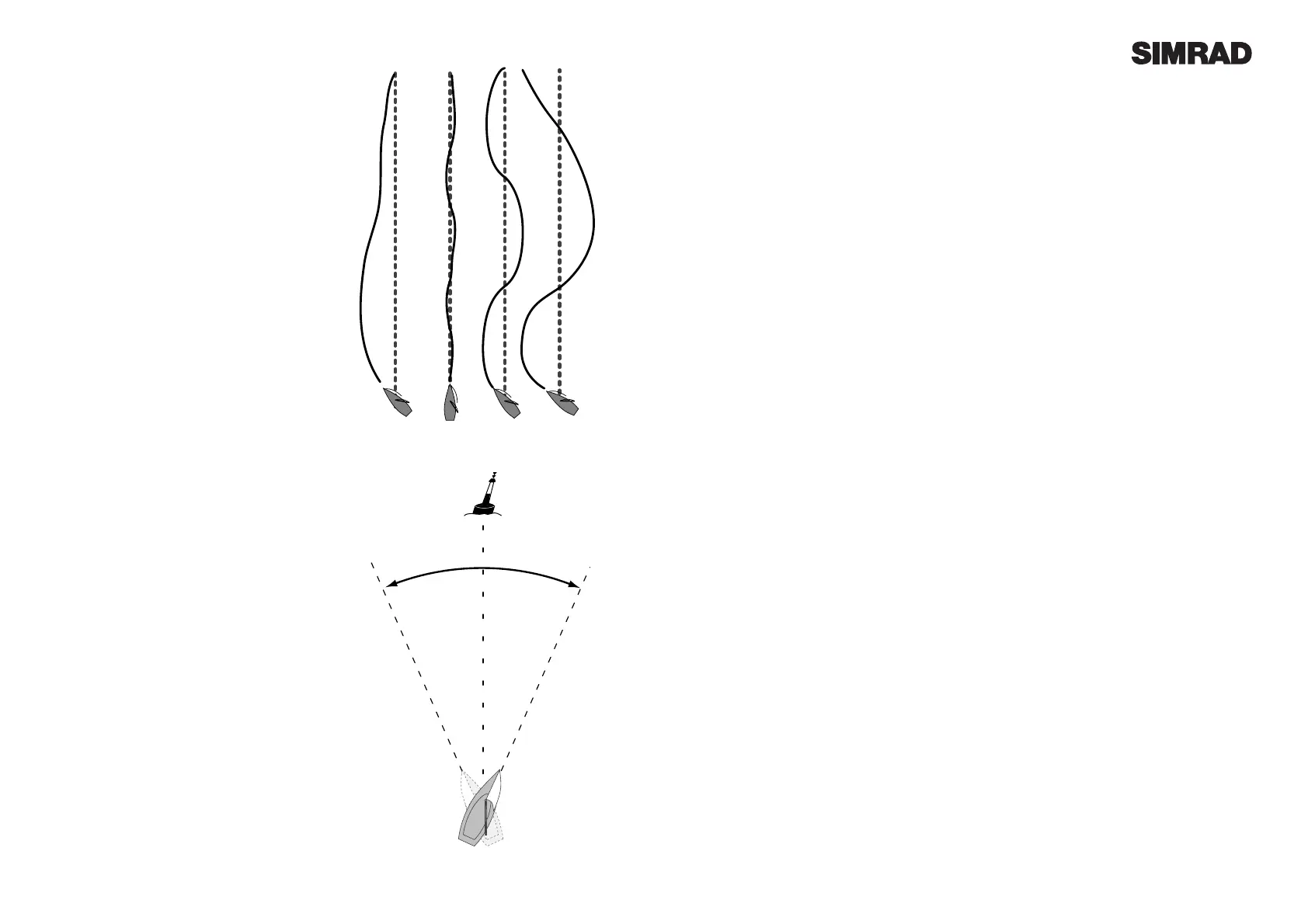

Fig 2.5A shows the effect of setting the Gain too

low: the boat takes a long time to return to the cor-

rect heading. Fig 2.5B is ideal, where errors are

quickly corrected. Fig 2.5C occurs when the Gain

too high, causing the boat to ÒSÓ, or oscillate

around the correct heading. Excessive Gain (Fig

2.5D) causes instability of course, leading to

increasing error.

To adjust Gain, please refer to section 4.3.

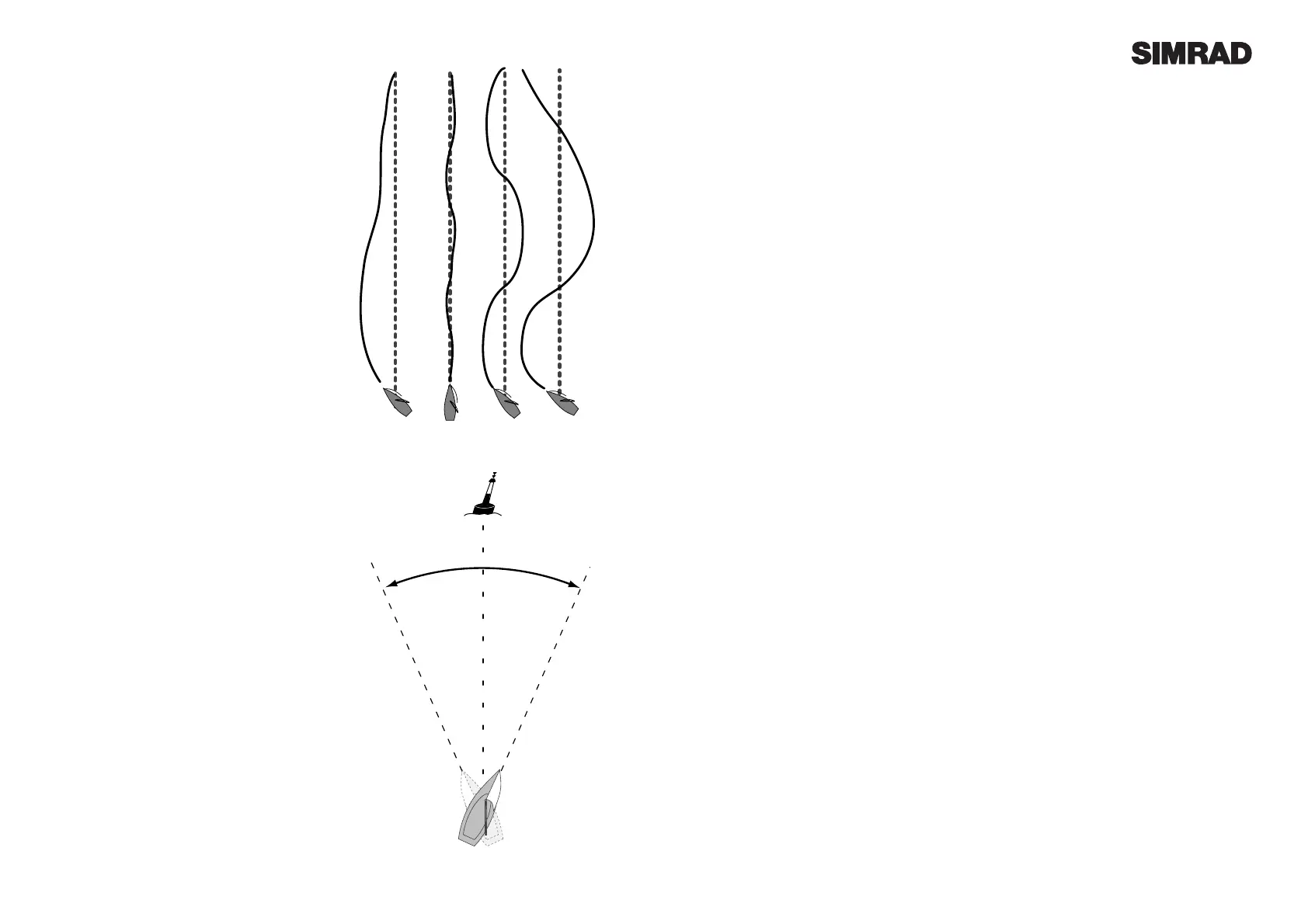

2.7 Seastate

In rough weather, more variations in heading will be

detected by the Wheelpilot due to the heavy seas

yawing the vessel. If no account of this was taken,

then the Wheelpilot would be overworked, causing

unnecessary strain on the unit and excessive drain

on the batteries. All Simrad Wheelpilots will contin-

uously monitor corrections applied to the wheel

over the course of a voyage, and allow a Òdead

bandÓ within which the boat can go off course with-

out corrections being made (Fig 2.6).

The dead band is automatically set and updated

by the Wheelpilot to give the best compromise

between course holding and battery consumption.

However, this can be manually set if so desired.

To manually adjust the Seastate, please refer to

section 4.4.

Fig 2.5 - Effects of Gain setting

2.8 Autotrim

Under differing conditions a rudder bias (sometimes known as standing helm or rudder trim) is

applied in order to steer a straight course. An example is when sailing close hauled where the ves-

sel will normally pull into the wind, and the helmsman applies a standing helm to leeward in order

to maintain course. The amount of this standing helm varies according to factors such as strength

of wind, boat speed, sail trim and amount of sail set. If no account of these were taken, then the

vessel would tend to veer off course, or pull round head to wind if sailing close hauled.

The Wheelpilot continuously monitors the average course error and applies a bias to the wheel to

compensate until the optimum condition is reached. This bias or standing helm is applied gradu-

ally, so as not to upset the normal performance of the Wheelpilot. Thus, it may take up to a minute

or so to fully compensate after changing tack. Once optimum trim is reached, the pilot will still

monitor for changes in the prevailing conditions and update the trim accordingly.

Loading...

Loading...