MOORE FANS LLC, Marceline, MO 64658 Phone (660 ) 376-3575 FAX (660) 376-2909

Page 13

TMC-647-(Rev E) - 01/06

4.2 BLADE OVERLOAD

Of all the aerodynamic abuses to be avoided in the

operation of a fan, the most important is that of overload-

ing the fan blades. Blade overload occurs because of

insufficient blade area: In other words, when there is an

inadequacy in the number of blades on the fan selected.

The Moore system of rating is based upon the pres-

sure that each blade will produce at a given RPM with good

efficiency. This pressure is called 100% blade load. When

blade load exceeds 110%, the fan will not only operate at

lower efficiency, it may be subject to structural damage as

well.

In selecting a fan, the total pressure divided by the

pressure to be produced by one blade determines the num-

ber of blades required for the anticipated performance.

Whenever information is available, The Moore Company

checks the selection. Even so, underestimation of the pres-

sure requirements by the system designer, or changes in the

operating conditions over time, may result in overload

conditions.

Why is a blade overload condition of such concern?

We are all aware of the fact that an airplane traveling at a

given speed can carry only a certain load. If the speed of the

airplane is decreased or the load increased, stalling flow

over the wing will occur. In the case of an airplane, approxi-

mately two-thirds of the lift provided by the wing is the

result of the air flow over the top or convex portion of the

wing. Lift is provided as a reaction to the flow of air being

accelerated and deflected downward as it passes over the

wing. A negative pressure area is thus formed on the top

surface of the wing which tends to lift it upward.

So long as air flow over the wing is smooth and clings

to the surface of the wing, little turbulence is present. When

the load is increased, or the speed decreased, the angle of

the wing to the air stream must be increased to a point

where the air flow breaks away from the upper surface of

the wing. This is known as stalling or burbling flow, since

the air, instead of clinging to the wing, breaks away near the

leading edge and leaves what might be called a turbulent

void above the upper wing surface, nullifying the acceler-

ated flow which was responsible for the greater part of the

lift of the wing.

When this occurs, the wing loses a large portion of

its lift. Flow, however, will re-establish briefly and break

again, the cycle being repeated continuously, resulting in a

severe vibration throughout the aircraft as the flow alter-

nately makes and breaks. Anyone who has experienced a

stall in an airplane will be familiar with this violent phe-

nomenon.

A fan blade is no different than an airplane wing

except that the air usually is being deflected upward rather

than downward, the convex side of the blade being the

lower surface rather than the upper surface as in the case of

an airplane. The result of blade overload is identical: When

blade load exceeds that allowable, a violent vibration will

take place in the blade as the laminar, or uniform, flow

makes and breaks perhaps many times a second.

Another way of looking at this problem is to consider

that the available number of blades are set at too steep an

angle to be able to move air at the axial velocity which is

necessary to maintain a smooth flow over the convex

surface. In other words, to move air at the velocity neces-

sary for this blade angle, plus overcoming the static resis-

tance of the system, the total pressure which would have to

be maintained for an air flow corresponding to this angle is

greater than the total pressure capability of the given

number of blades at this RPM. Such a condition can only

be corrected by decreasing the blade angle until smooth

flow is obtained or by increasing the number of blades and

the total pressure potential of the fan until the fan’s pres-

sure potential equals the pressure necessary to move the

specified quantity of air through the system.

Continued operation under conditions of stalling

flow, or blade overload, will significantly shorten the life of

the fan. Operation under these conditions will also reduce

efficiency to a ridiculously low figure. See the chart under

Section 4.4 Checking Blade Load which follows. Note that

although air flow remains constant or decreases, horse-

power continues to increase with increased blade angle.

In conclusion, if a given fan, in a given installation,

can only absorb forty horsepower, for example, the blades

may be pitched up to consume fifty horsepower without

any increase in air delivery, and possibly with a decrease.

As a result, the extra ten horsepower is totally wasted --

perhaps worse than wasted. It is good practice to select a

sufficient number of blades so that blade load will amount

to slightly less than 100% of full blade load when the motor

to be used as a driver is fully loaded. There are a number of

reasons for allowing this safety factor which are set out in

detail below.

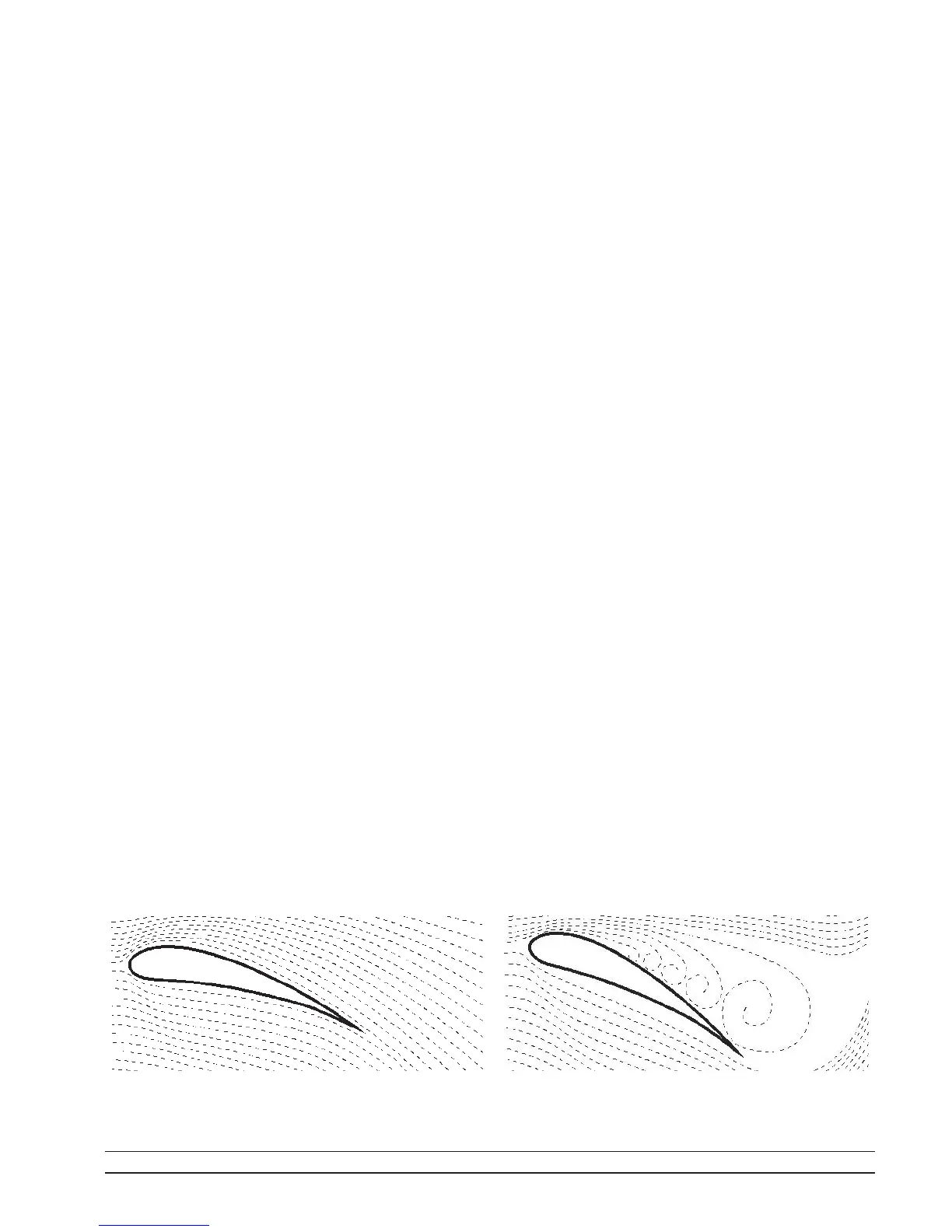

AIRFLOW IN NORMAL FLOW

Downward flow provides lift to the wing

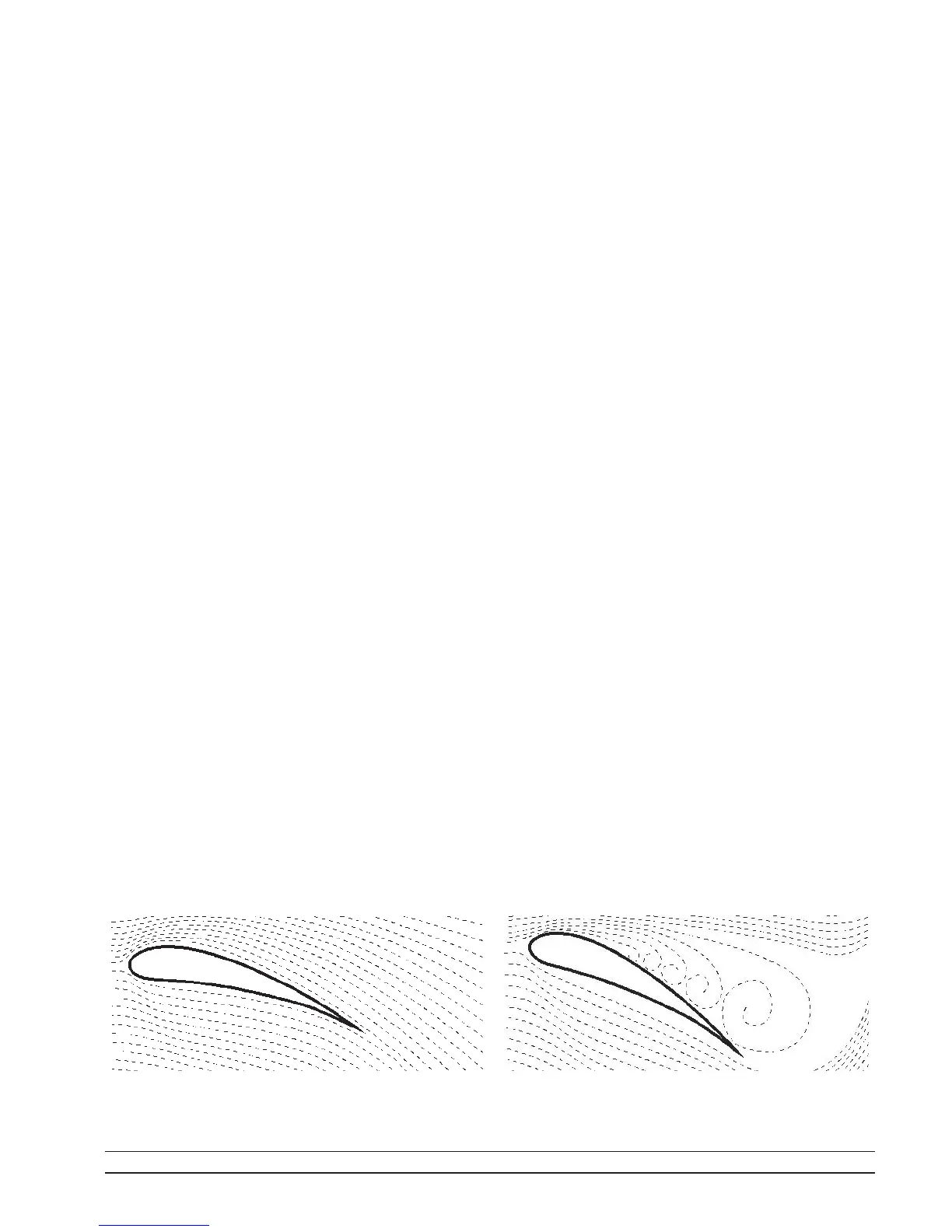

AIRFLOW IN STALLING FLOW

Note lack of air deflection downward.

OPERATION

Loading...

Loading...