It is thought that the Tracheal mites (also known as Acarine) were a

major contributory factor to the ‘Isle of Wight disease’, first seen in the

early 1900s. This decimated the honey bee population, later spreading

to mainland UK. In more recent times, the Tracheal mites have had a

serious economic impact on the beekeeping industry in North America,

after their introduction there in the 1980s from Mexico. However, in the

UK, Tracheal mite infection is not usually a serious disease, with relatively

small numbers of colonies being affected.

The honey bee delivers oxygen to body tissues via diffusion through a

complex system comprising of tubes, called trachea, and air sacs. It is in

these trachea that the acarine mites reproduce and feed. Mature female

mites enter the anterior thoracic spiracles of young bees (bees are only

susceptible to infestation within the first nine days after emergence). The

mites lay their eggs in the trachea and, upon hatching the larvae begin to

feed on the haemolymph (blood) of the bee. The larvae undergo several

moults before reaching their adult forms, and are then ready to infest

new hosts.

Symptoms and Cause

Acarapisosis is the infestation of the breathing tubes (trachea) of the adult

bee by the parasitic mite Acarapis woodi. In many cases, bees cluster in

front of the hive, appearing confused and disorientated, unable to return

to the hive. Some of the bees may also display what is known as ‘K-wings’,

where the rows of hooks holding pairs of the bee’s wings together

become detached. However, these abnormalities are not always seen and

may or may not necessarily be found in association with an infestation.

The main consequence of an infestation is to shorten the lifespan of

the overwintering bees. This may lead to ‘spring dwindling’, where

the winter bees die early in the spring. This means that the expanding

brood cannot be supported sufficiently and leads to the demise of the

colony. It has been suggested that if the colony goes into winter with

greater than a 30% infestation, then the colony is unlikely to survive.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The disease can only be diagnosed by carrying out a dissection

and microscopic examination (using a dissecting microscope with

up to x40 magnification) of the primary trachea. In a healthy,

or uninfested bee, the trachea will have a uniform, creamy-

white appearance. In infested bees, the trachea will show patchy

discolouration or dark staining, (melanisation, caused by mites feeding).

In addition, the eggs, nymphs and adult stages of the mite may also

be seen in the trachea. There are currently no approved treatments for

Acarine. The best method of control available to the beekeeper is to re-

queen colonies that are susceptible to the disease.

Tracheal mites

Two Nosema species have been identified in honeybees in England and

Wales; Nosema apis and, more recently, the Asian species Nosema ceranae.

Both are highly specialised parasitic Microsporidian fungal pathogens.

Nosema spp. invade the digestive cells lining the mid-gut of the bee, there

they multiply rapidly and, within a few days, the cells are packed with

spores, the resting stage of the parasite. When the host cell ruptures, it

sheds the spores into the gut where they accumulate in masses, to be

later excreted by the bees. If spores from the excreta are picked up and

swallowed by another bee, they can germinate and once more, become

active, starting another round of infection and multiplication.

Symptoms of Nosema

There are no outward symptoms of the disease. Dysentery is often

seen in association with N. apis infections; this may be seen as spots

of bee poo on the hive or across the frames. The dysentery is not

caused by the pathogen, but as a consequence of infection and can

be exacerbated during periods of prolonged confinement during

inclement weather, especially during the spring. This can lead to the bees

being forced to defecate in the hive, thereby contaminating it further.

In Spain it has been reported that N. ceranae infections are characterised

by a progressive reduction in the number of bees in a colony until the point

of collapse. The beekeeper may also see a significant decline in colony

productivity. In the final phase of decline, secondary diseases frequently

appear, including chalk brood and American foul brood. Eventually

the affected colonies contain insufficient bees to carry out basic colony

tasks and they collapse. Mortality in front of the hives is not a frequent

symptom of N. ceranae infection. Dysentery and visible adult bee mortality

in front of the hives are reported to be absent in N. ceranae infections.

Dwindling can sometimes be rapid or take place over several months.

Nosema is readily spread through the use of contaminated combs. The

spores can remain viable for up to a year, it is therefore important not to

transfer contaminated combs between colonies and, as always, to practice

good husbandry and apiary management, maintaining vigorous, healthy

stocks, which are better able to withstand infestations.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The simplest method of diagnosing infections is by microscopic

examination. Both N. apis and N. ceranae can be identified in adult

bee samples using a standard adult disease screen - under the light

microscope the spores of N. apis and N. ceranae appear as white/green,

rice shaped bodies. Both species are virtually identical when viewed

using conventional microscopy, but can be distinguished by an expert

eye. However, more accurate discriminatory tests are available which

detect differences between the two species using genetic methods.

Currently treatment with the antibiotic Fumidil B (available in the UK) is

an effective control against both Nosema species, for up-to-date advice

on the availability of medicines please visit the VMD (Defra’s Veterinary

Medicines Directorate) website www.vmd.gov.co.uk. As with all medicines

ensure that the label instructions are followed.

Nosema

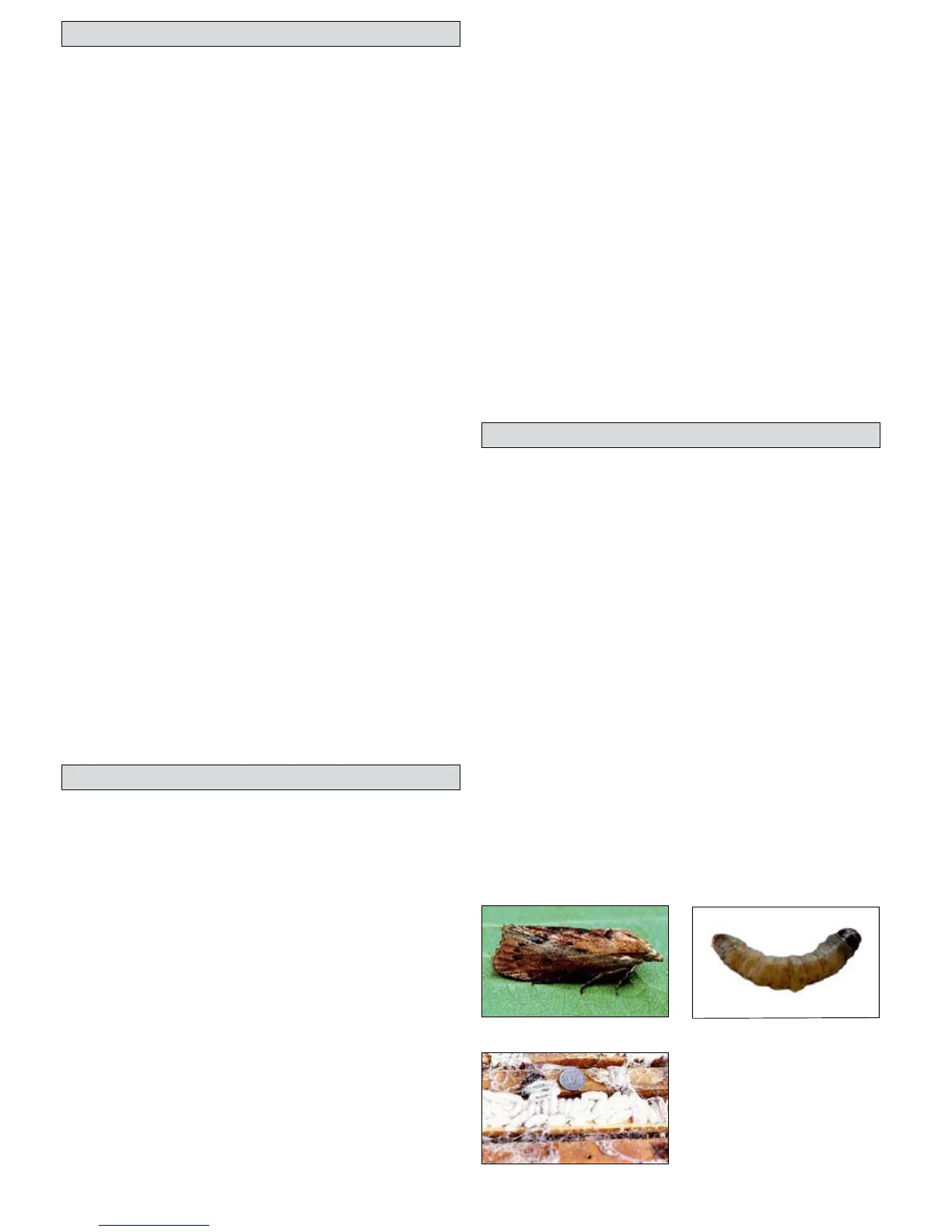

A wax moth larvae which causes

the damage.

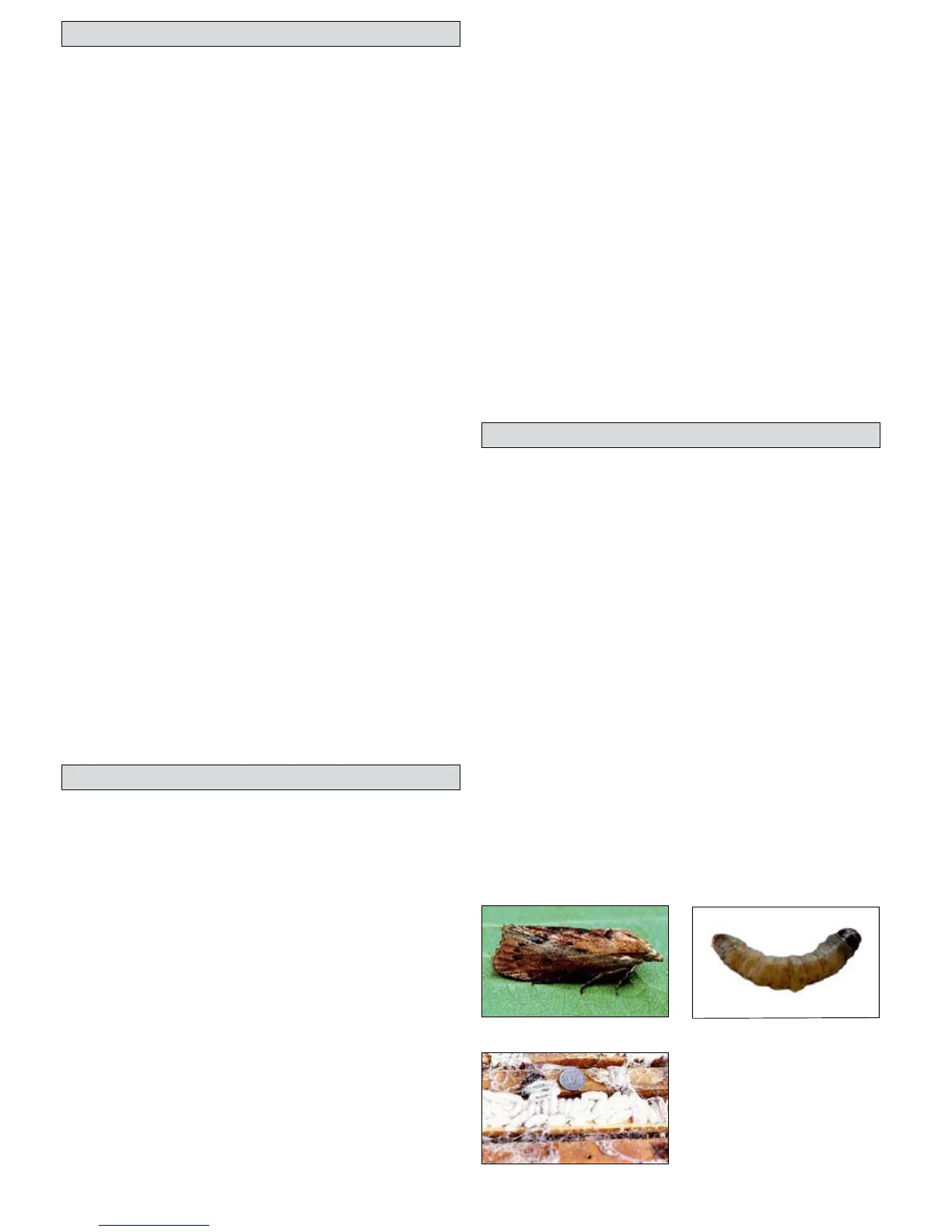

Wax moth cocoons on top of

some frames.

A wax moth larvae on a leaf.

In the UK, there are two species of moth which routinely lay their eggs in

bee hives and cause damage; the Greater Wax Moth - Galleria mellonella

and the Lesser Wax Moth Achroia grisella. Both species can be significant

pest of both hives and stored frames. However, the greater wax moth is

usually more of a problem.

Symptoms

The larvae of both species feed on the wax of combs. However, they cannot

survive on pure wax alone (those fed on pure bees wax have been shown

to stop developing), they also rely on other impurities within the wax -

particularly cocoons in old brood combs. The larvae will burrow through

the comb, leaving silk trails behind them and may also be seen moving

just below the cappings of brood. In extreme cases, the whole of the

comb will be destroyed, leaving a matted mass of silk, frass and other

debris. The wax moth, if left unchecked, can be particularly damaging

in dead colonies or in the apiary store. The greater wax moth can also

cause significant damage to wooden hive parts; they may chew out small

hollows in which to pupate.

Control

Good strong colonies will not usually tolerate infestation by wax moth and

it is usually not a problem in the field in healthy colonies. It is, however,

a problem in either weak colonies, hives where colonies have died, or in

stored combs. In the field, hives should be kept as strong and healthy

as possible, combs should not be left lying around the apiary and dead

colonies should be removed. Infested combs cannot be effectively treated

and should be burned. If you are storing frames with comb over winter

you should put them in the freezer at -20ºC for at least 48hrs to kill any

adults, larvae or eggs before being stored in a cold outside area.

Wax moth

Loading...

Loading...