Chapter

5. Macros

The assembler must encounter the macro definition before the first

call

for that macro. Otherwise, the macro

call

is

assumed to

be

an

illegal

opcode. The assembler inserts the macro body identified

by

the macro name

each time

it

encounters a

call

to a previously defined macro

in

your program.

The positioning

of

actual parameters

in

a macro

call

is

critical since the substitution of parameters

is

based

solely on position. The first-listed actual parameter replaces each occurrence of the first-listed dummy param-

eter; the second actual parameter replaces the second dummy parameter, and

so

on.

When

coding a macro call,

you must

be

certain to list actual parameters

in

the appropriate sequence for the macro.

Notice that blanks are usually treated

as

delimiters. Therefore, when

an

actual parameter contains blanks

(passing the instruction

MOY

A,M,

for example) the parameter must

be

enclosed

in

angle brackets. This

is

also

true for any other delimiter that

is

to

be

passed

as

part

of

an

actual parameter. Carriage returns cannot

be

passed

as

actual parameters.

If a macro call specifies more actual parameters than are listed

in

the macro definition, the extra parameters

are ignored.

If

fewer parameters appear

in

the

call

than

in

the definition, a null replaces each missing parameter.

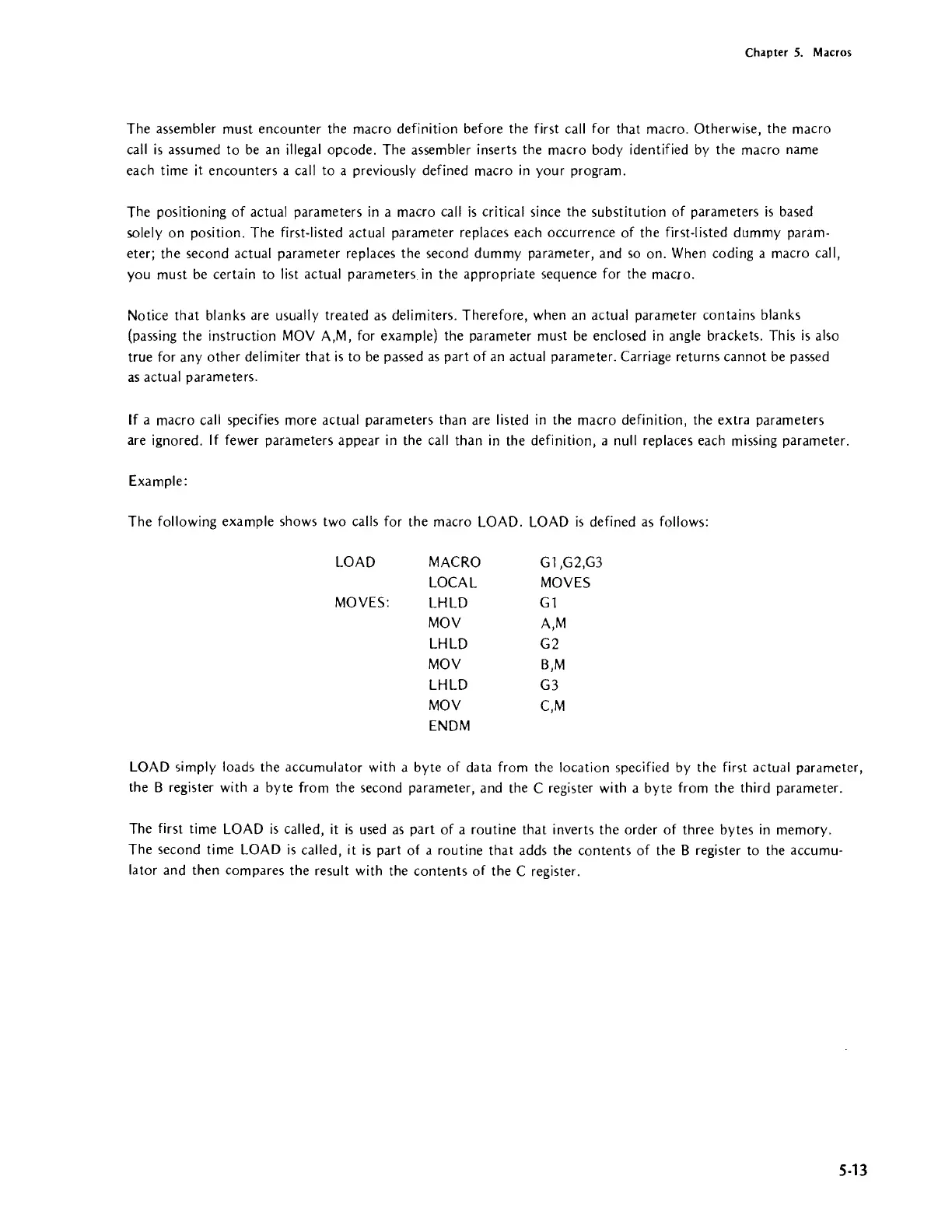

Example:

The following example shows two calls for the macro

LOAD.

LOAD

is

defined

as

follows:

LOAD

MACRO

Gl,G2,G3

LOCAL

MOYES

MOYES:

LHLD

Gl

MOY

A,M

LHLD

G2

MOY

B,M

LHLD

G3

MOY

C,M

ENDM

LOAD

simply loads the accumulator with a byte of data from the location specified

by

the first actual parameter,

the B register with a byte from the second parameter, and the

C register with a byte from the third parameter.

The first time

LOAD

is

called,

it

is

used

as

part of a routine that inverts the order of three bytes

in

memory.

The second time

LOAD

is

called, it

is

part of a routine that adds the contents

of

the B register to the accumu-

lator and then compares the result with the contents of the C register.

5-13

Loading...

Loading...