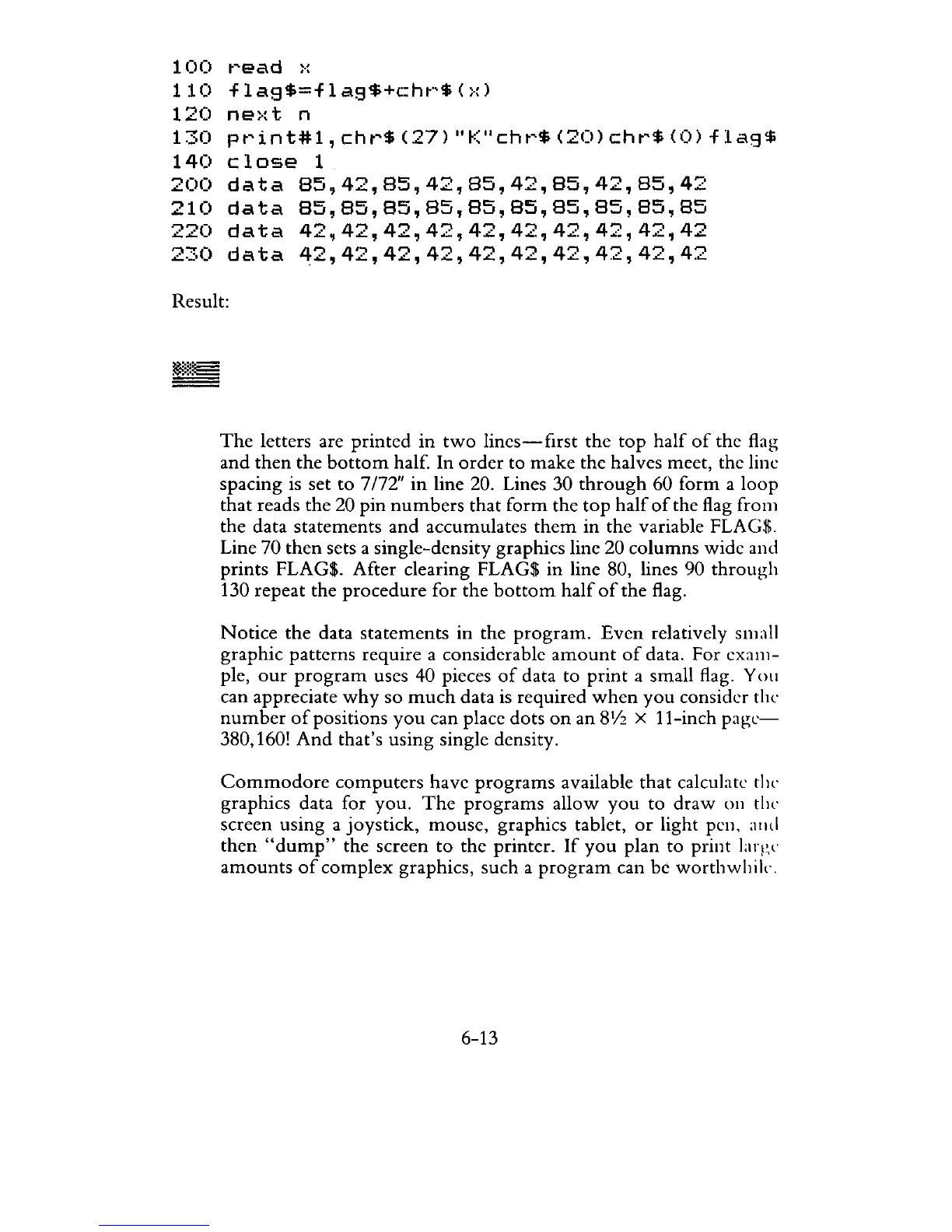

1

00

t~ead

:.:

110

fla8$=fla8$+chr$(x)

120

ne:·:t

n

130

pt~int#l,

cht~$

(27)

"I<"cht~$

(20)

cht~$

(0)

f

1a8$

140

close

1

200

data

85,42,85,42,85,42,85,42,85,42

210

data

85,85,85,85,85,85,85,85,85,85

220

data

42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42

230

data

42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42,42

Result:

The

letters are

printed

in

two

lines-first

the

top

half

of

the flag

and

then

the

bottom

half. In

order

to

make

the halves meet, the line

spacing is set

to

7/72"

in

line 20. Lines 30

through

60 form a loop

that

reads the 20 pin

numbers

that

form

the

top

half

of

the flag from

the data statements and accumulates

them

in

the variable FLAG$.

Line

70

then

sets a single-density graphics line 20 columns wide and

prints FLAG$. After clearing FLAG$ in line

80, lines 90

through

130 repeat the

procedure

for the

bottom

half

of

the flag.

Notice

the data statements in the

program.

Even

relatively small

graphic patterns require a considerable

amount

of

data. For

exam-

ple,

our

program

uses 40 pieces

of

data to

print

a small flag. Y

Oil

can appreciate

why

so

much

data

is

required

when

you

consider

thl"

number

of

positions

you

can place dots

on

an

8V2

X

II-inch

page-

380, 160!

And

that's using single density.

Commodore

computers

have

programs

available that calculate till'

graphics data for you.

The

programs

allow

you

to

draw

Oil

the

screen using a

joystick,

mouse, graphics tablet,

or

light

pm,

alld

then

"dump"

the screen

to

the printer.

If

you

plan to print large

amounts

of

complex

graphics, such a

program

can be

worthwhik.

6-13

Loading...

Loading...