Section 5 — Sampling

EPS-16 PLUS Musician's Manual

Looping

One of the fundamental challenges of sampling is to make efficient use of the

sampler's memory. You simply cannot sample the entire duration of every event.

Plus, you usually want a sound to continue playing as long as you're holding the

key down, regardless of how long the original event was. This is why we

employ Looping.

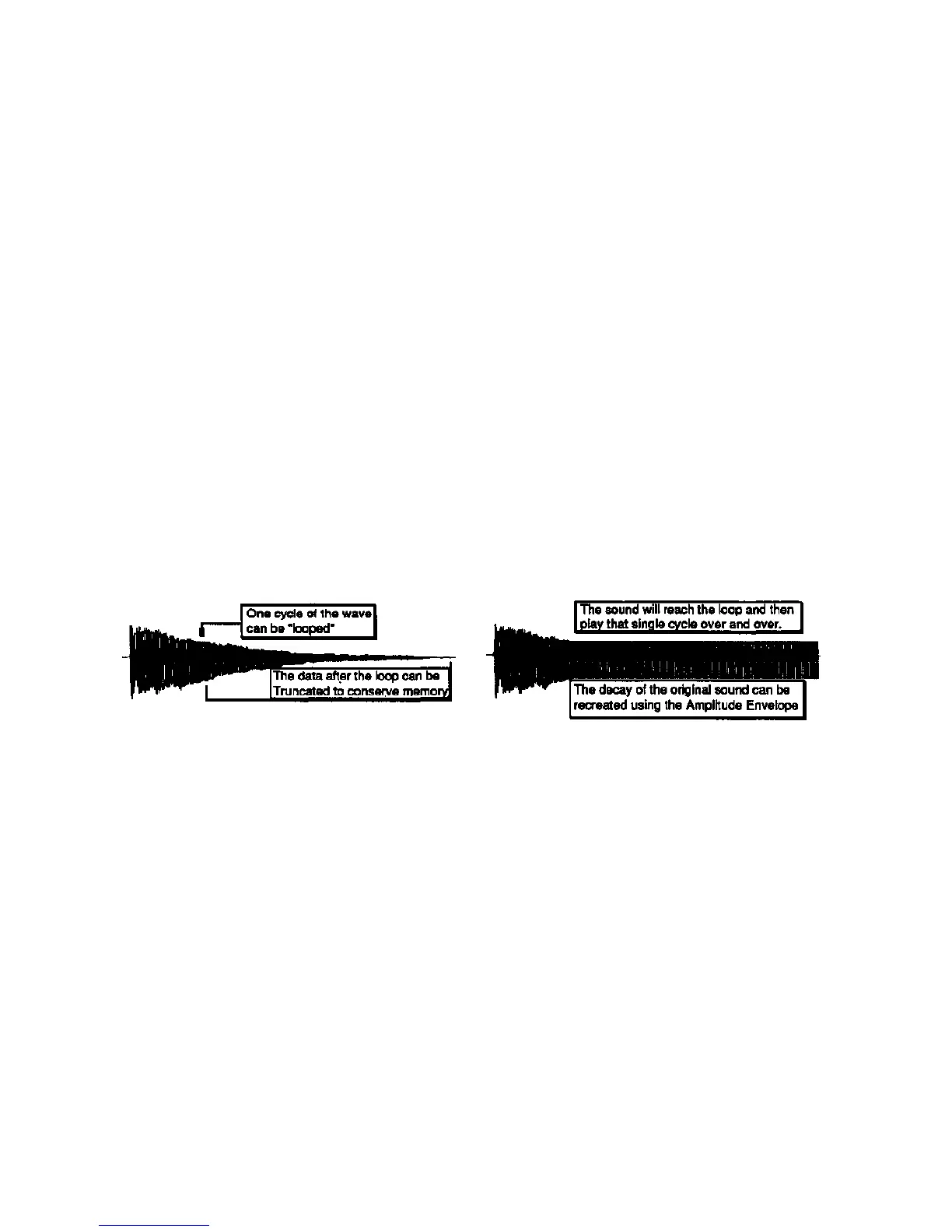

When we loop a segment of sound, what we are doing is playing through to the

end of the looped segment and then instantly starting back at the beginning of the

loop, as if playing one continuous sound. It's a lot like a tape loop—a segment

of recording tape with the two ends spliced together so that it cycles repeatedly.

Consider that a low note on a grand piano can last 30 seconds or more from the

time the key is struck to the time it decays into silence. Sampling this entire event

does not make sense because:

• You could use up all your sampling memory (and then some) on one note,

leaving no memory for multisampling; and

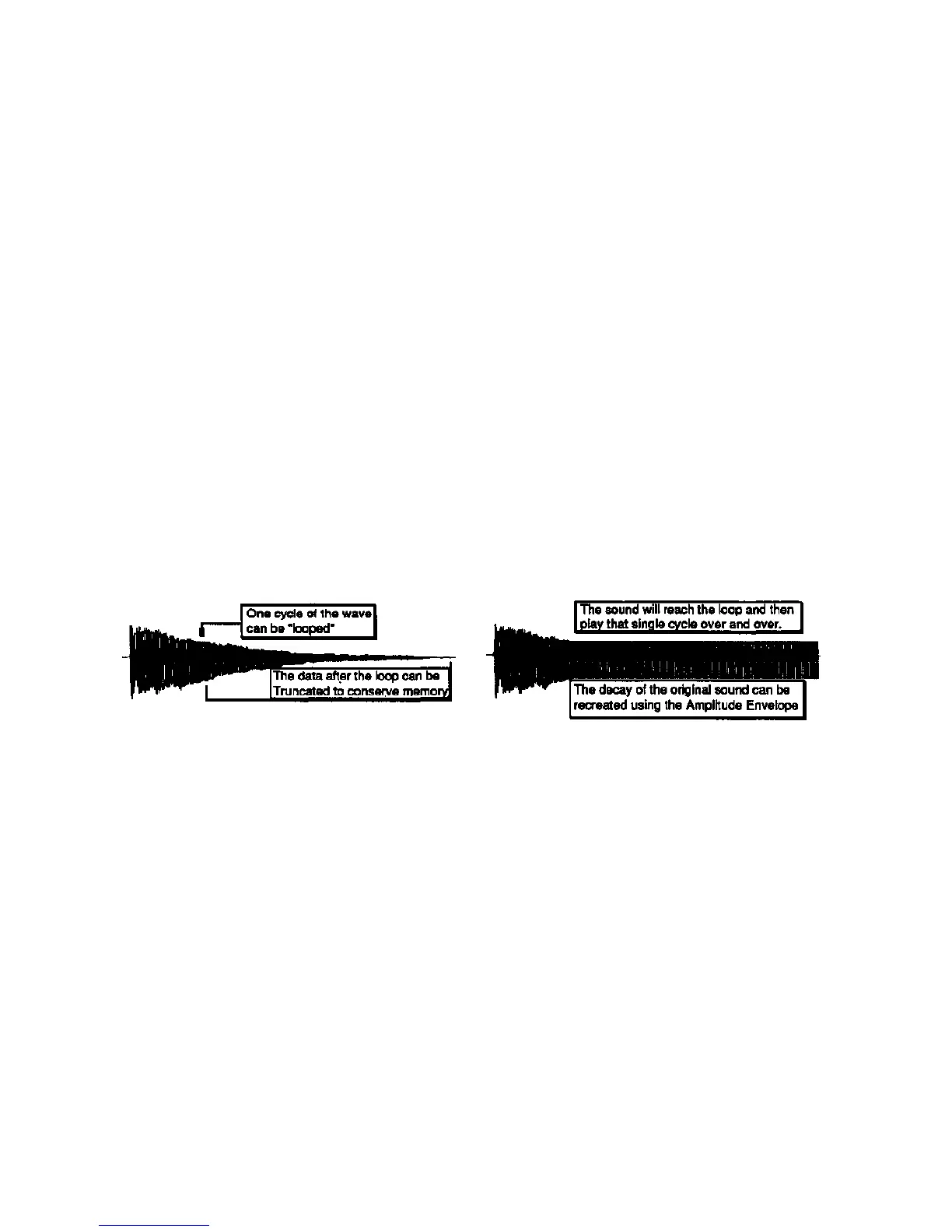

• After the initial attack transients die down, the sound of the piano string settles

into what is essentially a repeating waveform. This means that you can select

one cycle of this repeating waveform and loop it (play it over and over). All

the data after the loop can then be removed (truncated) because you don't need

it. This conserves memory.

A piano, solo violin, guitar, or woodwind are all sounds which you could loop in

this way. However, there are other sounds which do not settle into a repeating

waveform. A full pipe organ, string section or a choir would be good examples

of such sounds. These sounds remain extremely complex throughout their

duration. Using a single-cycle loop on a choir sample would cause the sound to

suddenly become very static and one dimensional when it reaches the looped

section. These complex, ever-changing sounds require that we employ longer

loops—repeating a large segment of the sound rather than just a single wavecycle.

Generally, successful loops fall into one of two categories—single-cycle loops,

which we refer to as short loops, and loops of about a second or more, which we

call long loops. Which type to use depends on the sound. If the sound settles

into something relatively static, use a short loop. If the sound is composed of

many elements which constantly chorus and interact with each other over time,

you will need to use a long loop.

5 - 12

Loading...

Loading...