351

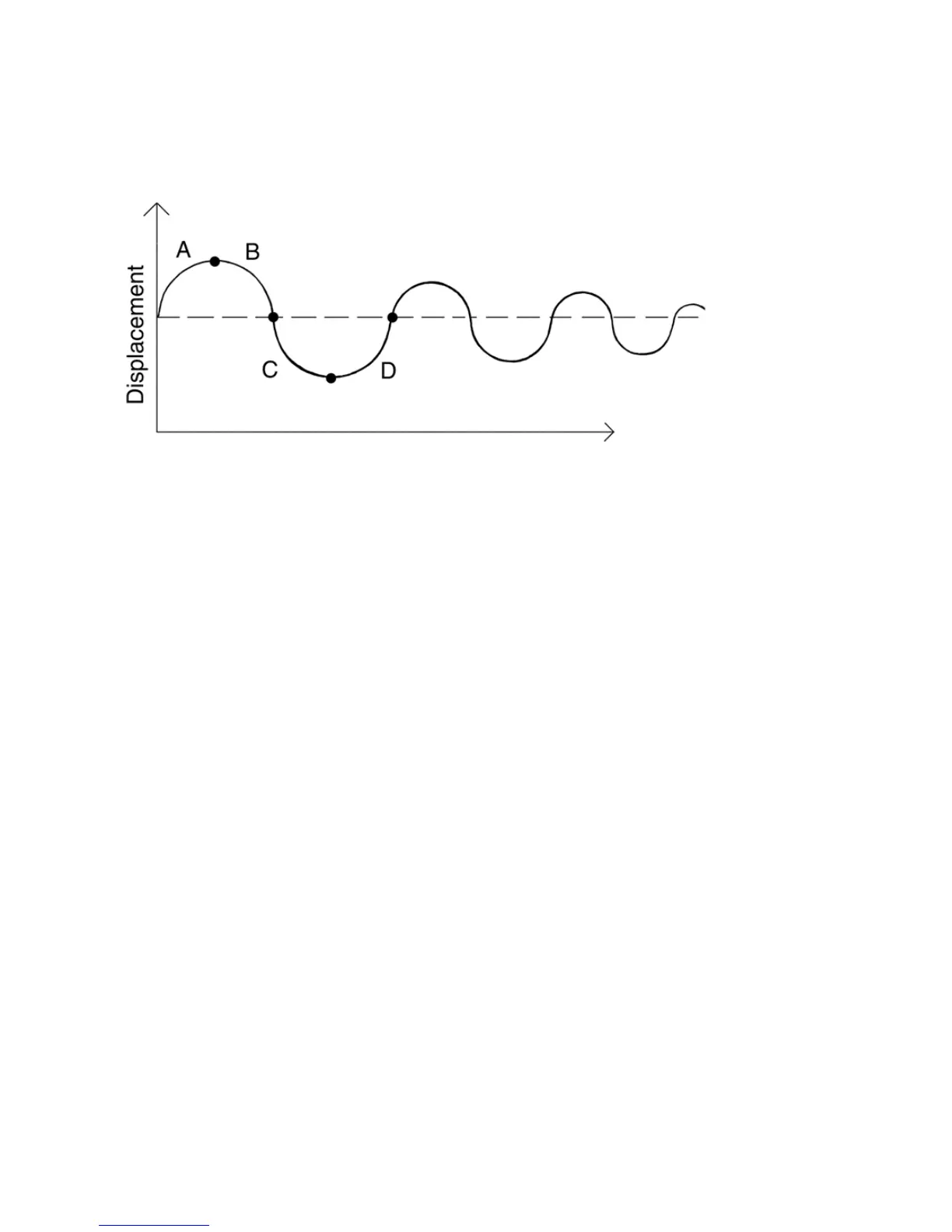

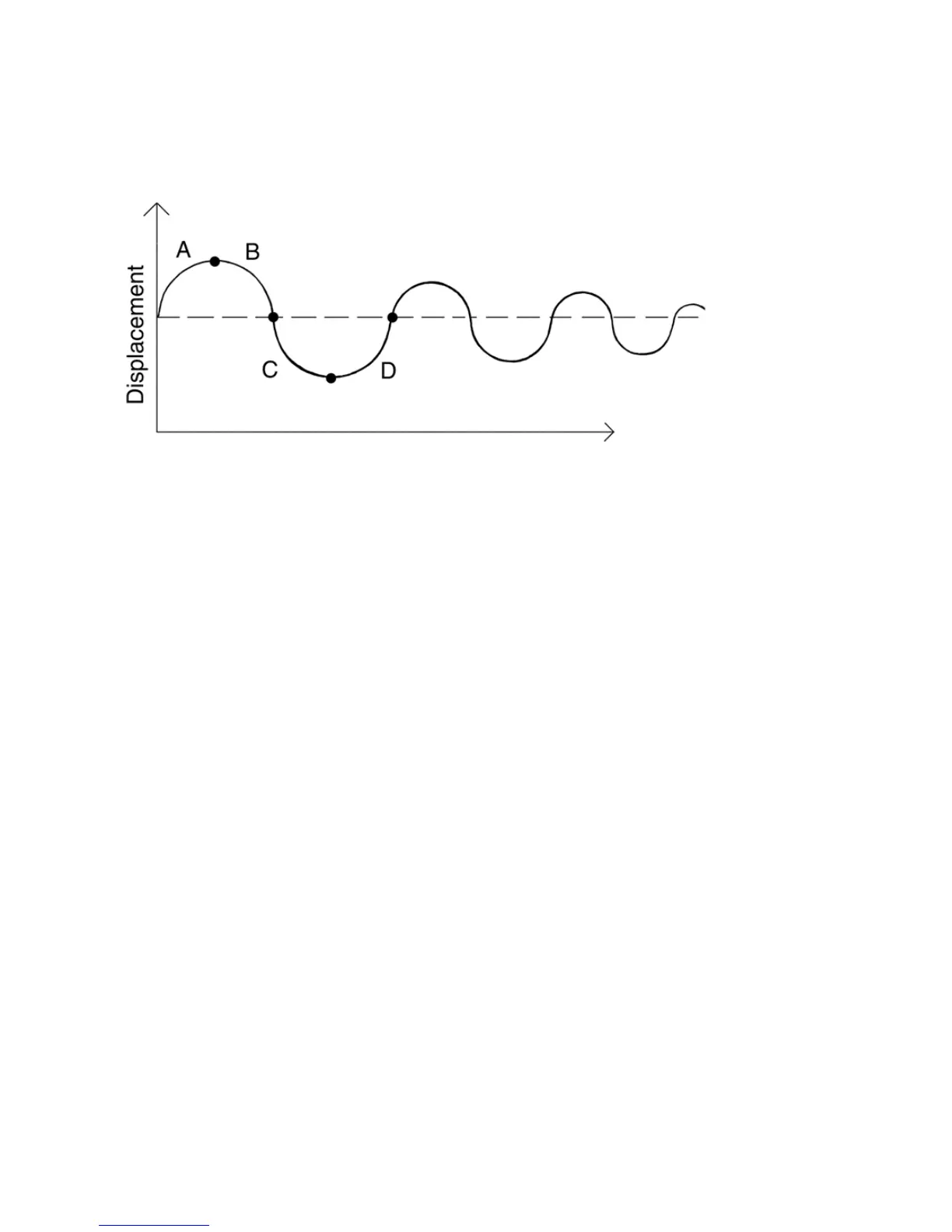

The displacement of the string changes as the string vibrates, as shown here:

The segment marked “A” represents the string as it is pulled back by the pick; “B”

shows it moving back towards its resting point, “C” represents the string moving

through the resting point and onward to its outer limit; then “D” has it moving

back towards the point of rest. This pattern repeats continuously until the friction

of the molecules in the air gradually slows the string to a stop. As the string

vibrates, it causes the molecules of air around it to vibrate as well. The vibrations

are passed along through the air as sound waves. When the vibrations enter your

ear, they make your eardrum vibrate, and you hear a sound. Likewise, if the

vibrating air hits a microphone, it causes the microphone to vibrate and send out

electrical signals.

In order for us humans to hear the sound, the frequency of the vibration must be

at least 20 Hz. The highest frequency sound we can hear is theoretically 20 kHz,

but, in reality, it's probably closer to 15 or 17 kHz. Other animals, and

microphones, have different hearing ranges.

If the simple back-and-forth motion of the string was the only phenomenon

involved in creating a sound, then all stringed instruments would probably sound

much the same. We know this is not true, of course; the laws of physics are not

quite so simple. In fact, the string vibrates not only at its entire length, but at one-

half its length, one-third, one-fourth, one-fifth, and so on. These additional

vibrations (overtones) occur at a rate faster than the rate of the original vibration

(the fundamental frequency), but are usually weaker in strength. Our ear

doesn't hear each frequency of vibration individually, however. If it if did, we would

hear a multinote chord every time a single string were played. Rather, all these

Loading...

Loading...